LispFlat

(How to Write a (Lisp) Interpreter (in C#))

LispFlat: A C# port of Peter Norvig’s Toy Lisp

Introduction

This is a quick port to C#, from Python, of Peter Norvig’s famous lis.py toy Lisp (Scheme) interpreter.

The primary purpose of this project was to build an interpreter - again - having not written one in years. I want to revisit Lisp and there is no better way, than to write an interpreter, to remind oneself as to the basics!

Secondly, I enjoy learning about code and, surprisingly, still find that it is easier to translate from Python to C# rather than from C or C++, two languages I used to know very well! This toy project was no different (although if check my links at the end I would say that F# is easy too, but why would. one bother to port from F# to C#?). As you will see here, the code quite reasonably mirrors python with some caveats, of course.

Finally, it is important to note the original code is a toy interpreter that is, it is a toy. It has very little error checking with very limited functionality (with which you can still go surprisingly far) and this project mirrors those limitations too. It is a fun and not a professional project. Later, Peter enhanced this with lisp.py, I might one day revisit this project and update it to that level, but that is not for today.

Development

This post can be read in a standalone fashion but you might find it useful to read Peter’s notes on his project first.

Now, whist not playing code golf, it was still my intent to get this solution to be as small as reasonably possible. I could not hope to reach Peter’s less than 90 lines of code but this solution is around 180 lines of code including tests and the console test harness, not bad going from a dynamic to statically typed language and one with a poor type system and poor type inference compared to, say, F#. I have even retained Peter’s original comments and most of the variable names, where possible and useful.

Exp

The code follows much of the original format except, not being dynamically typed, an Exp (Expressions) class was added, to handle the different types of S-Expressions - atoms, lists and procedures.

This has atoms: double for numbers (the python has integers as well); string is used as

the symbol type (for labeling atoms, lists and procedures); bool (#t and #f- that are

not in the Python) has been added; a type to handle the procedures ; and a List<Exp> for lists

and to recursively store the whole Abstract Syntax Tree.

internal enum Type { Num, Bool, Sym, List, Proc }

internal class Exp

{

public string Sym { get; }

public double Num { get; }

public bool Is { get; }

public List<Exp> List { get; }

public Func<Exp, Env, Exp> Proc { get; }

public Type Type;

// Atoms

public Exp(string sym) { Sym = sym; Type = Type.Sym; }

public Exp(double dbl) { Num = dbl; Type = Type.Num; }

public Exp(bool @bool) { Is = @bool; Type = Type.Bool; }

// lists

public Exp(List<Exp> exp) { List = exp; Type = Type.List; }

public Exp(IEnumerable<Exp> exp) { List = exp.ToList(); Type = Type.List; }

// procs

public Exp(Func<Exp, Env, Exp> inv) { Proc = inv; Type = Type.Proc; }

// wrappers

public static Exp Func(Func<Exp, Env, bool> proc) => new Exp((a, e) => new Exp(proc(a, e)));

public static Exp Func(Func<Exp, Env, double> proc) => new Exp((a, e) => new Exp(proc(a, e)));

public static Exp Func(Func<Exp, Env, IEnumerable<Exp>> proc) => new Exp((a, e) => new Exp(proc(a, e)));

public static Exp Func(Func<Exp, Env, Exp> proc) => new Exp(proc);

// list ops

public int Count => List?.Count ?? -1;

public Exp this[int i] => List[i];

// "Numbers become numbers; true/false becomes bools; every other token is a symbol."

public static Exp Atom(string token)

{

if (double.TryParse(token, out double resDbl))

return new Exp(resDbl);

if (token == "#t")

return new Exp(true);

if (token == "#f")

return new Exp(false);

if (token == "") // nil or ()

return new Exp(new List<Exp>(0));

return new Exp(token);

}

public override string ToString()

{

if (Type == Type.Bool)

return Is ? "#t" : "#f";

if (Type == Type.Num)

return Num.ToString();

if (Type == Type.Sym)

return Sym;

if (Type == Type.Proc)

return "<function>"; ;

if (Type == Type.List)

return Count > 0 ? $"({string.Join(" ", List.Select(i => i.ToString()))})" : "";

return "stringify error";

}

}

This uses both atoms (Sym, Bool and Num) and List here but not Scheme’s pairs. In Scheme, the empty list

() (nil in Lisp) is both an atom and a list, here it is only a list. Note that it is explicitly

captured in Atom().

This solution uses the .Net List<T> type as the underlying data structure for Lisp lists. This

is obviously inefficient, especially seeing (later) both: how cdr is implemented - as

List.Skip(1).ToList() and that cons uses Linq’s Prepend() onto a List<Exp> which is inefficient

since, unlike Lisp, where the prepend operation is cheap (using single linked lists), it is the Append/Add operation

that is cheaper with .Net List<T>. (Lisp encourages prepends (cons) over appends for both design and

performance).

The pain point was the need to use wrappers to handle the differing output types from

Standard Procedures, which are represented as Func<Exp,Env,Exp> and the need to

wrap those again, in order to store them in the same Environment dictionary (see below) as other

Symbol Expression pairs. (With more time than allowed for this project, a better solution might be

developed).

Finally, it was more logical to move a couple of methods in the original python into this class. These were the lisp string output from the REPL and the atom function used to create atom Exp types.

Environment Dictionary

//"An environment: a dict of {'var':val} pairs, with an outer Env."

internal class Env : Dictionary<string, Exp>

{

Env _outer;

public Env(Exp parms = null, Exp args = null, Env outer = null)

{

if (parms != null)

foreach (var (parm, arg) in parms.List.Zip(args.List, (p, a) => (p.Sym, a)))

Add(parm, arg);

_outer = outer;

}

//"Find the innermost Env where var appears."

public Env Find(string var) =>

TryGetValue(var, out Exp val) ? this:

_outer != null ? _outer.Find(var)

: throw new LispException($"Lookup {var} failed");

}

This is the environment dictionary structure that holds the keys to all the standard procedures, as well as all the user defined operations for named lists and atoms and also named lambdas and their argument parameter bindings.

On this last point, it is the optional args that are needed for local function scoping of lambdas - assigning values to function arguments. This is the purpose of the zip. This will be discussed when we get to Lambdas below. This is why there are nested environments, so that the local lambda scope does not pollute the general environment and that the lambda has its arguments bound in the current context.

(Also added was a minor extra piece of error checking, it was really useful to see key misses in debugging).

(Parse(Tokenize(Read)))

// Read a Scheme expression from a string

internal static Exp Parse(string program) => ReadFromTokens(Tokenize(program));

// Convert a string to a queue of tokens

static Queue<string> Tokenize(string s)

{

if (s == null)

throw new LispException("no code");

return new Queue<string>(s.Replace("(", " ( ").Replace(")", " ) ")

.Split(new char[] { ' ' }, StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries));

}

// Read an expressions from a sequence of tokens

static Exp ReadFromTokens(Queue<string> tokens)

{

if (!tokens.Any())

throw new LispException("unexpected EOF while reading");

var token = tokens.Dequeue();

if ("(" == token)

{

var L = new List<Exp>();

while (tokens.Peek() != ")")

L.Add(ReadFromTokens(tokens));

tokens.Dequeue(); // ")"

return new Exp(L);

}

else if (")" == token)

throw new LispException("unexpected ')' ");

else

return Exp.Atom(token);

}

This is the first half of the core of an interpreter. It very similar to the Python.

The Tokenize() function is incredibly simple, not even any regexps are needed! This is

partly due to the simple and consistent syntax of S-Expressions. A more sophisticated implementation could not be as simple

but this is an elegant tokenizer.

The parser reads these tokens into the relevant Exp types. The nested lists are loaded into

List<Exp> which is, itself, a type in Exp. Note that the empty list () creates an empty List<Exp>

which is a translation of the empty string "". This must be captured in Atom() and was the source of some

mischief in debugging.

The simplicity of this solution means that parsing is performed on per line entered basis, so no multi-line lisp can be used (that can be done from files as can be seen later in the Tests section).

Standard Environment

//"An environment with some Scheme standard procedures."

internal static Env StandardEnv() => new Env

{

["*"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num * a[1].Num),

["+"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num + a[1].Num),

["-"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num - a[1].Num),

["/"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num / a[1].Num),

["%"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num % a[1].Num),

["<"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num < a[1].Num),

["="] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num == a[1].Num),

[">"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Num > a[1].Num),

[">="] = Exp.Func((a, e) =>a[0].Num >= a[1].Num),

["<="] = Exp.Func((a, e) =>a[0].Num <= a[1].Num),

["append"] = Exp.Func((a,e)=> a[0].List.Concat(a[1].List)),

["car"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].List.First()),

["cdr"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].List.Skip(1)),

["cons"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[1].List.Prepend(a[0])),

["length"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Count),

["list"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a),

["list?"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a.Type == Type.List),

["not"] = Exp.Func((a, e) =>!a.Is),

["null?"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a[0].Count==0),

["number?"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a.Type == Type.Num),

["procedure?"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a.Type == Type.Proc),

["symbol?"] = Exp.Func((a, e) => a.Type == Type.Sym),

};

You will notice there are fewer standard procedures than in the Python, but the above was enough to pass all the tests plus add some additional tests.

No attempt was made to add in System.Math, which was a 1 liner in Python (but not automatically tested

although at least some of those functions do work in the original). Note that the math

procedures are binary or dyadic and not n-ary. I did not check if the original handles n-ary

operations but that can be done with map in this solution.

There were other procedures that were removed that were not tested nor worked in the

python such as map and apply. These were added back in, written as Lisp lambdas, as part

of the test suite!

The subtlety here is understanding Lisp’s lists. At this level, there is a single list of arguments.

Prior to this, the first item in the list was symbol that has been called here, these arguments are the

cdr of that list. So, these are now a list of arguments to the called symbol procedure. All

these standard procedures use either 1 or 2 arguments a[0] and a[1] (n-ary could trivially be added,

there just aren’t any coded for here). The logic of append/cons/car/cdr and so on should now

make sense.

Read-Eval-Print-Loop

static Env _globalEnv;

//"A prompt-read-eval-print loop."

public static void Repl(string prompt = "list.cs", Env env =null)

{

_globalEnv = env ?? StandardEnv();

Title = prompt;

while (true)

{

Write(prompt + ">");

var val = Eval(Parse(ReadLine()), _globalEnv);

var str = val.ToString();

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(str))

WriteLine(str);

}

}

The only aspect that needs to be explained is the handling of Env.

Eval(Parse(ReadLine()), _globalEnv) can be called in this Repl() function and also by

test.cs. There is a wrapper around both in static main() in program.cs so that they can share

the same environment. So the tests double up as a loader of some prepared user procedures. (see further

in debugging below).

Eval

//"Evaluate an expression in an environment."

internal static Exp Eval(Exp x, Env env)

{

if (x.Type == Type.Sym) // variable reference - special forms below

return env.Find(x.Sym)[x.Sym];

else if (x.Count < 1) // constant literal - Num or Bool

return x;

else if (x[0].Sym == "quote") // (quote exp)

return x[1];

else if (x[0].Sym == "if") // (if test conseq alt)

{

var (test, conseq, alt) = (x[1], x[2], x[3]);

var exp = Eval(test, env).Is ? conseq : alt;

return Eval(exp, env);

}

else if (x[0].Sym == "define") // (define var exp)

{

var (var, exp) = (x[1], x[2]);

env[var.Sym] = Eval(exp, env);

return new Exp(""); //nop

}

else if (x[0].Sym == "set!") // (set! var exp)

{

var (var, exp) = (x[1], x[2]);

env.Find(var.Sym)[var.Sym] = Eval(exp, env);

return new Exp(""); //nop

}

else if (x[0].Sym == "lambda") // (lambda (var...) body )

{

var (parms, body) = (x[1], x[2]);

return Procedure(parms, body, env);

}

else if (x[0].Sym == "begin") // (begin exp+)

{

Exp last = null;

foreach (var exp in x.List.Skip(1))

last = Eval(exp, env);

return last;

}

else // proc arg

{

var proc = Eval(x[0], env);

var args = from exp in x.List.Skip(1) select Eval(exp, env);

return proc.Proc(new Exp(args), env);

}

}

//"A user-defined Scheme procedure."

static Exp Procedure(Exp parms, Exp body, Env env) => new Exp((Exp args, Env e) => Eval(body, new Env(parms, args, env)));

This is the second half of the core of an interpreter (along with the Env environment dictionary). It closely mirrors the Python.

Surprisingly this took very little puzzling to create nor to debug.

Once a decent (ish) Exp data structure had been determined, it was very quick to get a running interpreter! The bulk of the work then was working on some issues in some of the standard procedures, which took longer than getting the basic skeleton to work.

The two important pieces to understand here, what are ‘special forms’ and how do the lambdas - a specific special form - work? Given the previous question, it is reasonable to first discuss ‘special forms’.

Special Forms (and Lambdas)

When Eval() runs recursively and it finds a Symbol in the first position of a list, it

then calls the environment dictionary and evaluates and returns the keyed value. This can be an

atom, list or function.

In the case of an atom being returned, the next recursive evaluation is dealt with in the

second else if (x.Count<1) ( a count of zero is the empty list and is treated here as an atom).

When one ends up at the else clause, where the list, for that is what it must be then,

contains a prefix function followed by a number of arguments. That is the standard form.

The function is at position x[0]. The remaining list items are the arguments which are collected and then the relevant procedure (standard or user)

is invoked.

The other else if clauses contain the ‘special forms’: ‘quote’, ‘if’, ‘define’, ‘set!’

(mutable ‘define’) and ‘begin’. These are ‘special’ because not all parameters are evaluated first

before being bound to arguments to run a standard procedure: ‘if’ selectively evaluates its arguments,

‘quote’ returns its argument unevaluated, and so on.

The final and interesting ‘special form’ is ‘lambda’. This contains two lists - the first of parameters at x[1]

and the body of the lambda at x[2]. For example in (lambda (a) (+ a a)) x[0]=”lambda”,

x[1]=(a) a list with one item ‘x’ and in x[2] a the body, in this case a 3 element list - a normal procedure (addition).

This constructs a Procedure() which returns a lambda which, when invoked - by Eval later -

updates the local environment through which it binds arguments to the expected parameters

of the lambda. This construct is invoked in the same way as any standard normal form function

via the default else clause.

The Python works differently, creating an instance of a class that can be directly invoked with arguments (not a method of that instance). The difference between the two approaches is clear by last code line (“A user-defined Scheme procedure.”) above, which returns a (C#) lambda.

Debugging

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Env env = null;

if (args.Length == 1)

{

env = Lisp.StandardEnv();

try

{

Tests.Run(env);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

Console.Read();

}

}

while (true)

{

try

{

Lisp.Repl("lisp.cs",env);

}

catch (LispException ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

Console.Write("Enter 'y' to exit else return to restart: ");

if ('y' == Console.Read())

Environment.Exit(0);

}

}

}

}

This setup brought back memories of (my) old school C/C++ programming days in the 80s and early 90s when I ran the tests in the process of launching a console app (as a library harness or standalone).

Sharing the standard environment and having the tests run - success or failure - enables one to use the Repl to further investigate the issue under question and test procedures are already available in the Repl!

Very usefully in debugging this, I had installed Racket and Python so I could run both the

original code and compare both this and the original to some decent dialect of Scheme (Racket in this case)

Not only is there cut and paste between the test output and the repl, but I can compare and

contrast the limited operations of lis.py with Scheme.

I have to emphasize that lis.py is quite buggy with very limited error handling. The use of program.cs

here enables one to have a similar development experience working with lis.py running in

Python in a console (I used IDLE to be precise).

This code mirrors lis.py in the sense that only additional code needed to get it to pass the original tests were added.

The gotchas were some normal form functions that did not work even on lis.py, hence they ended up being removed here.

The worst gotcha was a classic. The first test, what was for quote, returned an extra set of enclosing

brackets and every now and then there in other tests there appeared to be strange extra spaces

before some closing brackets. I ignored this and this led me to some quite unnecessary lost time!

I should have fixed it as soon as I saw it. I failed my own test first principles here. It is not just balancing brackets that is important in Lisp but all those spare or redundant

brackets and spaces (of course you would never see them in a production List system). Ultimately,

via (not..) and (nul? ..), this was due to (quote ()) - quoting an empty string, a critical phrase in many algorithms to quit out of a recursion, as

you can see in the tests below.

Testing

static Dictionary<string, string> _testAll = new Dictionary<string, string>

{

["(quote (testing 1 (2.0) -3.14e159))"] = "(testing 1 (2) -3.14E+159)",

["(+ 2 2)"] = "4",

["(+ (* 2 100) (* 1 10))"] = "210",

["(if (> 6 5) (+ 1 1) (+ 2 2))"] = "2",

["(if (< 6 5) (+ 1 1) (+ 2 2))"] = "4",

["(define x 3)"] = "",

["x"] = "3",

["(+ x x)"] = "6",

["(begin (define x 1) (set! x (+ x 1)) (+ x 1))"] = "3",

["((lambda (x) (+ x x)) 5)"] = "10",

["(define twice (lambda (x) (* 2 x)))"] = "",

["(twice 5)"] = "10",

["(define compose (lambda (f g) (lambda (x) (f (g x)))))"] = "",

["((compose list twice) 5)"] = "(10)",

["(define repeat (lambda (f) (compose f f)))"] = "",

["((repeat twice) 5)"] = "20",

["((repeat (repeat twice)) 5)"] = "80",

["(define fact (lambda (n) (if (<= n 1) 1 (* n (fact (- n 1))))))"] = "",

["(fact 3)"] = "6",

["(fact 50)"] = "3.04140932017134E+64",

["(define abs (lambda (n) ((if (> n 0) + -) 0 n)))"] = "",

["(list (abs -3) (abs 0) (abs 3))"] = "(3 0 3)",

["(not #f)"] = "#t",

["(length (list 1 2 3))"] = "3",

["(length ())"] = "0",

["(null? ())"] = "#t",

["(null? (list 0))"] = "#f",

["(begin (define a (list 1 2 3 4)) a)"] = "(1 2 3 4)",

["(car a)"] = "1",

["(cdr a)"] = "(2 3 4)",

["(car (cdr (cdr a)))"] = "3",

["(define combine (lambda (f)"+

"(lambda (x y)"+

"(if (null? x) (quote ())"+

"(f (list (car x) (car y))"+

"((combine f) (cdr x) (cdr y)))))))"] = "",

["(cons (list 1) (list 2 3))"] = "((1) 2 3)",

["(cons 1 (list 2 3))"] = "(1 2 3)",

["(define zip (combine cons))"] = "",

["(zip (list 1 2 3 4) (list 5 6 7 8))"] = "((1 5) (2 6) (3 7) (4 8))",

["(append (list 1) (list 2 3))"] = "(1 2 3)",

["(append (list 1 2) (list 3))"] = "(1 2 3)",

["((combine append) (list 1 2 3 4) (list 5 6 7 8))"] = "(1 5 2 6 3 7 4 8)",

["(define riff-shuffle (lambda (deck) (begin "+

"(define take (lambda (n seq) (if (<= n 0) (quote ()) (cons (car seq) (take (- n 1) (cdr seq))))))"+

"(define drop (lambda (n seq) (if (<= n 0) seq(drop (- n 1) (cdr seq)))))"+

"(define mid (lambda (seq) (/ (length seq) 2)))"+

"((combine append) (take (mid deck) deck) (drop (mid deck) deck)))))"] = "",

["(riff-shuffle (list 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8))"] = "(1 5 2 6 3 7 4 8)",

["((repeat riff-shuffle) (list 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8))"] = "(1 3 5 7 2 4 6 8)",

["(riff-shuffle (riff-shuffle (riff-shuffle (list 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8))))"] = "(1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8)",

["(begin " +

"(define map (lambda (fn seq) (if (null? seq) (quote ()) (cons (fn (car seq)) (map fn (cdr seq))))))" +

"(map (lambda (x) (+ x x)) a) )"] = "(2 4 6 8)",

["(begin " +

"(define reduce (lambda (fn init seq) (if (null? seq) init (fn (car seq) (reduce fn init (cdr seq))))))" +

"(reduce + 0 a) )"] = "10"

};

//"For each (exp, expected) test case, see if eval(parse(exp)) == expected."

internal static void Run(Env env = null)

{

// var fails = 0;

foreach (var (x, expected) in _testAll.Select(kvp => (kvp.Key, kvp.Value)))

{

ForegroundColor = ConsoleColor.Gray;

var result = Eval(Parse(x), env);

var ok = (result.ToString() == expected);

if (expected != "")

Write($"{x} => {result}");

else

Write($"{x} => None");

if (!ok)

{

ForegroundColor = ConsoleColor.Red;

WriteLine($" !! => {expected} ");

ForegroundColor = ConsoleColor.Gray;

}

else

WriteLine();

}

}

This has a simple test harness, optionally (by a command line argument) run before I can reach the Repl(). Apart from the cost of ignoring some of the tests, this worked very well for this project. (If I took it more seriously this is not the way I would recommend it). It was fun to go back to the way I tested in the 80s and early 90s.

Note that apart from some higher-order functions such as zip, already being in the original

test suite, I added some more tests including the last two being map and reduce. I am guessing it

was easier getting them to work in LispFlat than it would have been to write and test in the

C# interpreter. Well both took less than 5 minutes together here and that seemed a good time to stop

this project!

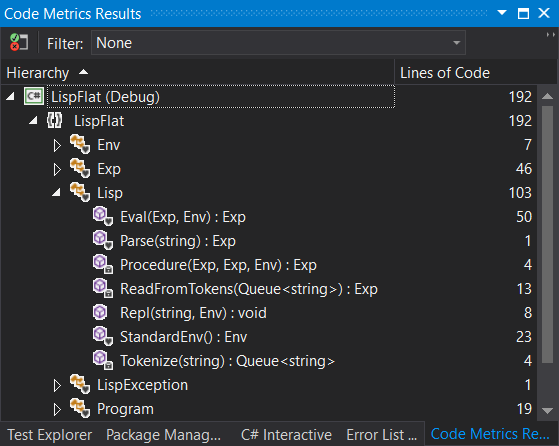

Lines of Code

As you can see the whole solution including tests and test harness is a total of 192 lines. Not bad compared to Python all things considered!

Conclusion

Well I hoped you enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed creating this solution.

Apart from the already linked to original by Peter Norvig there are also C++ and, on git-hub, F# solutions available, to compare.

Finally you can browse my source directly and fork it if you want!